The Relations between Diffuse and Performance-Specific Trust with Reform: A Research Report

العلاقة بين الثقة السائدة والخاصة بالأداء مع الاصلاح: تقرير بحثي

Introduction

The Middle East and North Africa region boasts populations whose pride in their nations remains at a high level. The region also enjoys a youth cohort with tremendous energy, entrepreneurship, and endurance, which otherwise is unfortunately and mistakenly labeled as “the youth bulge”. Such a cohort has worked tirelessly to improve their livelihoods and the conditions of their respective countries, whether in the form of collective activism or individual work. In this report, we sought to explore the relations between nationalism or national pride and youth’s tendency to admit to the existence of an issue and in turn, reform or change.

مقدمة

تشهد منطقة الشرق الأوسط وشمال أفريقيا بنسب عالية من القومية والانتماء للوطن، كما تتمتع المنطقة أيضًا بفئة شبابية ذات طاقة هائلة وفكر ريادي ومثابرة، وإن كان ذلك، لسوء الحظ، يشار إليه بشكل سلبي. ولكن الحقيقة أن الشباب عمل بلا كلل لتحسين سبل معيشهم وظروف بلدانهم، سواء على شكل نشاط جماعي أو عمل فردي. وسعينا في هذا التقرير إلى استكشاف العلاقات بين القومية أو الانتماء للوطن وميول الشباب في الحديث عن القضايا التي تواجه بلدانهم، بما في ذلك الإصلاح أو التغيير.

Methodology

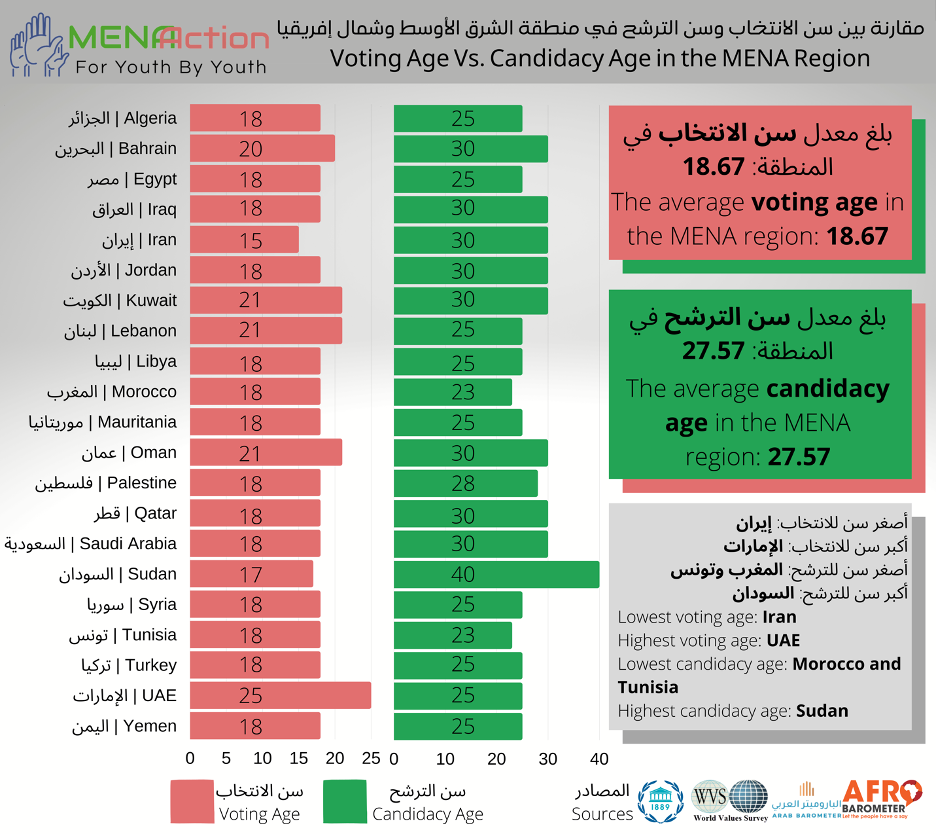

For this research, we examined data gathered by the World Values Survey, the Arab Barometer, the Afro Barometer, and the Arab Center. The data examined reflects a youth cohort of the individual countries, aged 18-30, as part of nationally representative samples. In examining the data, we further curated them on a scale of 1 to 4, whereby 1 was the lowest and 4 was the highest on the scale:

· 1 = do not trust at all/ no confidence at all;

· 2 = do not trust to an extent/ low level of confidence;

· 3 = trust to an extent/ moderate level of confidence;

· 4 = trust to a great extent/ very high level of confidence

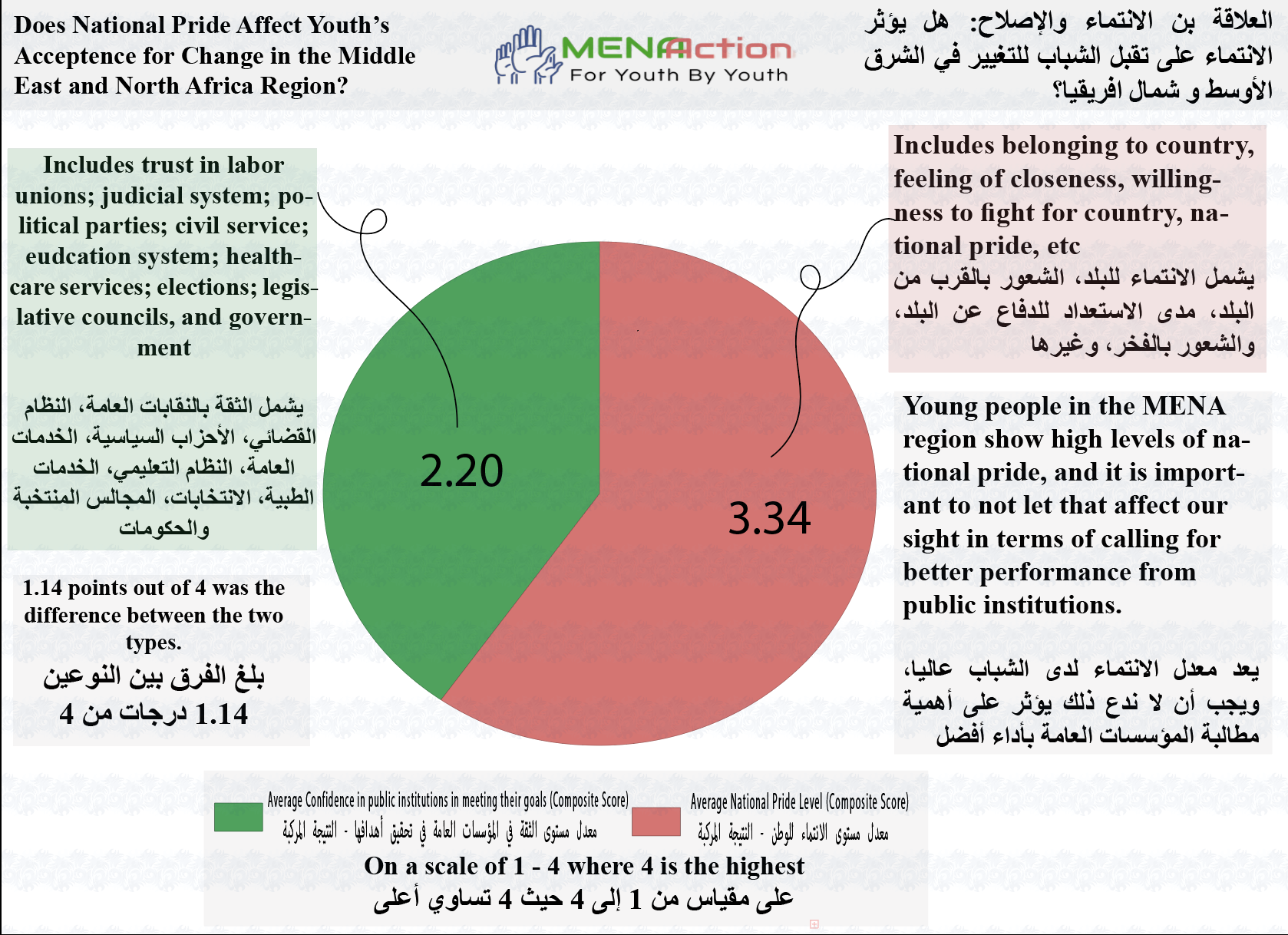

Public confidence or trust was defined as inclusive of two types. The first type delved into people’s attachment to country symbols as the level of belonging to their individual states, which can be labeled as diffuse support. The second type reflects public trust or confidence in the performance of public institutions in meeting their objectives.

المنهجية

قمنا بجمع بيانات من مصادر مفتوحة مثل "مسح القيم العالمي"، و "الباروميتر العربي"، و " الباروميتر الافريقي"، والمركز العربي. وتمثل البيانات التي تم دراستها آراء الشباب في المنطقة، والذين تتراوح أعمارهم بين 18 و30 عامًا، حيث يمثلونا جزءا من عينات تمثيلية على المستوى الوطني. وعند دراسة البيانات، قمنا بتحليلها على مقياس من 1 إلى 4، حيث كان 1 هو الأدنى و4 كان الأعلى على المقياس، وذلك على النحو الآتي:

· 1 = لا أثق على الاطلاق؛

· 2 = لا أثق إلى حد ما/ مستوى منخفض من الثقة؛

· 3 = أثق إلى حد ما/ مستوى معتدل من الثقة؛

· 4 = أثق إلى حد كبير/ مستوى عال جدا من الثقة

تم تعريف الثقة أو الثقة العامة على أنها شاملة لنوعين. يتعمق النوع الأول في ارتباط الناس برموز الدولة كمستوى الانتماء إلى بلدانهم، ويشار إلى هذا النوع على أنه "الثقة السائدة". أما النوع الثاني، فيعكس ثقة الأشخاص في أداء المؤسسات العامة في تحقيق أهدافها.

لإثبات الفرضيات الواردة في هذا التقرير أو تفنيدها أو تعديلها، يجب إجراء بحث متعمق مع أسئلة أكثر تفصيلاً وتحديدًا وذلك لفحص هذه البيانات للوصول إلى فهم أفضل فيما يتعلق بكيفية مناقشة الشباب للمشكلات في بلدانهم وعلاقة ذلك مع توجهاتهم فيما يتعلق بالإصلاح ليتم تحليل ذلك من منظور مستوى القومية أو الانتماء الوطني لديهم. ويمكن أن يكون مثل هذا البحث مصحوبًا بدراسة رصد بمشاركة الشباب من جنسيات مختلفة في المناقشة مع بعضهم البعض ومقارنة توجهاتهم في مجموعات متجانسة مع مجموعات تشمل جنسيات أخرى، الأمر الذي قد يحفز مستويات القومية والانتماء الوطني لديهم. وإلى ذلك، يتطلع هذا التقرير إلى بدء مناقشة حول هذه المسألة والانخراط مع الشباب في المنطقة في نقاش حول الإصلاح.

Diffuse Trust and Performance-Specific Confidence

Looking at individual countries’ youth populations’ trust levels revealed interesting findings. The individual scores of diffused trust and performance-specific confidence were aggregated under composite scores for each category. The first category included indicators such as national pride level, trust in the armed forces, affinity with the nation, and willingness to fight for country, among others. The second category included an evaluation of the performance of the governments, the legislative councils, the judiciary, the healthcare system, the educational system, among others.

With that, Algerian youth illustrated a diffuse trust/ national pride level of 3.19 out of 4, compared to only 1.82 level of performance-specific confidence, with a 1.37 difference in favor of the first. Bahrain’s youth national pride level was a little lower with 2.90, about 0.65 higher than its confidence in public institutions with 2.25. As for Egypt, a 3.50 national pride level, compared to 1.92 confidence level in public institutions, which stood 1.58 points below the first. Iranian youth showed similar pride levels to Egypt, but indicated slightly higher public confidence with 2.4, about 1 point lower than its pride levels. Iraqi youth’s pride levels stood at 3.38, almost double its 1.66 confidence in public institutions. Jordanian youth’s diffuse trust was the second highest in the region with 3.75, contrasted by a 2.08 confidence level.

As for Kuwaiti youth, their diffuse trust stood at 3.28, compared to their 2.18 performance-specific trust. Lebanese youth’s pride level with slightly higher than Kuwait’s with 3.35, but it was lower in terms of specific trust with 1.88, with a 1.47 difference between the two categories.

Libyan and Mauritanian youth scored very similar diffuse trust levels with 3.24 and 3.29, respectively, compared to a 1.72 and 1.96 performance-specific confidence levels, with Mauritanian youth illustrating some moderate levels of confidence, especially in terms of civil service. Moroccan and Mauritanian youth boasted identical levels of diffuse trust with 3.32, but Oman’s public confidence in the performance of institution higher than Morocco’s with 2.67 compared to 1.69 for the later, mostly due to Omani youth’s satisfaction with its healthcare services. Data for Palestinian youth was harder to find, given their circumstances. Their diffuse trust stood at 2.92, as the second lowest in the region, while their performance-specific confidence appeared exactly in the middle of the scale with 2. Qatari youth indicated the highest levels of confidence in both categories with 3.87 diffused trust and 3.55 for the second category, due to their high satisfaction with civil service, judiciary, and even the government.

Saudi Arabian youth showed similar patterns to that of Qatar, with a 3.69 diffused trust level, compared to a 3.03 performance specific trust. It is also worth noting that such a number might have been higher if it were not for moderate confidence in labor unions. Sudanese youth’s diffuse trust stood at 3.06, contrasted with a 2.01 performance-specific trust levels, as its government, elections, political parties, and parliament all evaluated under 2 points. Similar to Palestine, data for Syria was somewhat difficult to gather, so we relied on slightly older data. Nevertheless, Syrian youth indicated a diffuse trust level of 2.88, compared to a 1.55 performance-specific confidence, which was the lowest among the countries studied, with a notable 0.93 confidence level in civil services.

الثقة السائدة والثقة الخاصة بالأداء

كشفت دراسة مستويات ثقة الشباب في المنطقة عن نتائج مثيرة للاهتمام. حيث تم تجميع الدرجات الفردية للثقة السائدة والثقة الخاصة بالأداء وحساب معدلهم ضمن الدرجات المركبة لكل فئة. فتضمنت الفئة الأولى مؤشرات مثل مستوى الاعتزاز بالوطن، والثقة في القوات المسلحة، والانتماء للوطن، والهوية الوطنية، ومدى القابلية للدفاع عن الوطن، من بين أمور أخرى. أما الفئة الثانية فقد تضمنت تقييم أداء الحكومات والمجالس التشريعية والقضاء ومؤسسات الرعاية الصحية والنظام التعليمي وغيرها.

بالنظر إلى النتائج، بلغ مستوى الثقة السائدة أو مستوى الانتماء لدى الشباب الجزائري 3.19 من 4، مقارنة بمعدل الثقة الخاصة بالأداء والذي بلغ 1.82، أي 1.37 نقطة أقل من الفئة الأولى. وكان مستوى الفخر الوطني للشباب في البحرين أقل قليلاً حيث بلغ 2.90، وكان أعلى بنحو 0.65 نقطة من ثقتهم في المؤسسات العامة والتي بلغت 2.25. أما بالنسبة لمصر، فقد بلغ مستوى الانماء للوطن 3.50، مقابل 1.92 فيما يتعلق بالثقة بالمؤسسات العامة، والتي استقرت 1.58 نقطة دون الفئة الأولى. وأشار الشباب الإيراني إلى مستويات انتماء مماثلة لمصر، لكنهم أشاروا إلى نسب أعلى فيما يتعلق بالثقة بالمؤسسات العامة والتي بلغت 2.4، أي أقل بمقدار نقطة واحدة من مستويات الانتماء لديهم. واستقرت مستويات الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب العراقي عند 3.38، أي ضعف ثقتهم بالمؤسسات العامة والتي بلغت 1.66. وكانت الثقة السائدة للشباب الأردني ثاني أعلى مستوى في المنطقة حيث بلغت 3.75 مقارنة بمستوى ثقة بلغ 2.08 نقطة في المؤسسات العامة.

أما بالنسبة للشباب الكويتي، فقد بلغت ثقتهم السائدة 3.28 مقارنة بثقتهم الخاصة بالأداء البالغة 2.18. وأما بالنسبة للشباب اللبناني، فكان معدل الثقة السائدة لديهم أعلى بقليل من الكويت بـ 3.35، لكنه كان أقل من حيث الثقة الخاصة بالأداء والذي بلغ 1.88، وبفارق 1.47 نقطة من أصل 4 نقاط بين الفئتين.

سجل الشباب الليبي والموريتاني مستويات ثقة سائدة متشابهة جدًا بلغت 3.24 و3.29 على التوالي، مقارنة بمستويات الثقة الخاصة بالأداء والتي بلغت على التوالي 1.72 و1.96، حيث قيم الشباب الموريتاني أداء بعض المؤسسات بشكل معتدل، لا سيما فيما يتعلق بالخدمة المدنية. وبلغت مستويات الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب المغربي والموريتاني 3.32 نقطة من أصل 4 نقاط، ولكن ثقة الشباب العماني في أداء المؤسسات كان أعلى من الشباب المغربي بـ 2.67 نقطة مقارنة بـ 1.69 نقطة، ويرجع ذلك في الغالب إلى رضا الشباب العماني عن خدمات الرعاية الصحية. وكان من الصعب العثور على بيانات خاصة بالشباب الفلسطيني، وذلك بالنظر إلى ظروفهم، ولكن أشارت البيانات التي وجدناها إلى معدل ثقة سائدة بلغ 2.92 نقطة، كثاني أدنى مستوى في المنطقة، في حين بلغت ثقتهم الخاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة في منتصف المقياس بالضبط. وفيما يتعلق بالشباب القطري، كانت مستويات الثقة لديهم أعلى من باقي الدول، وفي كلا الفئتين، وذلك ب 3.87 نقطة فيما يتعلق بالثقة السائدة و3.55 نقطة للثقة الخاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة، حيث أشاروا إلى رضا كبير عن الخدمة المدنية والقضاء وحتى الحكومة.

وكانت مستويات الثقة لدى الشباب السعودي مشابهة لتلك الموجودة في قطر، حيث بلغ مستوى الثقة السائدة لديهم 3.69 نقطة، مقارنة بمعدل ثقة خاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة بلغ 3.03 نقطة. وتجدر الإشارة أيضًا إلى أن هذا المعدل كان من الممكن أن يكون أعلى لولا مستوى الثقة المنخفضة نسبيا في النقابات العمالية. وبلغت مستوى الانتماء الوطني أو الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب السوداني 3.06 نقطة، مقارنة بمستويات الثقة الخاصة بالأداء 2.01 نقطة، حيث تم تقييم الحكومة والانتخابات والأحزاب السياسية والبرلمان تحت نقطتين من أصل أربع. وعلى غرار فلسطين، كان من الصعب إلى حد ما جمع البيانات الخاصة بسوريا، لذلك اعتمدنا على بيانات أقدم قليلاً. ومع ذلك، أشار الشباب السوري إلى مستوى ثقة سائدة بلغت 2.88 نقطة، مقارنة مع مستوى ثقة خاص بالأداء يبلغ 1.55 نقطة، والذي كان الأدنى بين البلدان التي شملتها الدراسة، مع مستوى ثقة منخفض جدا بنسبة 0.93 في الخدمات المدنية.

وكان معدل الانتماء الوطني أو الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب التونسي مرتفعًا وذلك بمعدل 3.46 نقطة، أي حوالي 1.75 نقطة أعلى من الثقة الخاصة بالأداء، والتي بلغت 1.75 من أصل أربع نقاط. وكانت معدلات الانتماء أو الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب التركي 3.23 نقطة، مقارنة بمستوى ثقة بلغ 2.55 نقطة في أداء مؤسساتهم العامة، وإن كانت معدلات الثقة في القضاء عالية نسبيا. وبلغ معدل الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب الإماراتي 3.64 نقطة في المرتبة الرابعة، بعد قطر والأردن والسعودية، وجاء معدل ثقتهم في الأداء في المرتبة الثانية حيث بلغت 3.35 نقطة، بعد قطر 3.55. وأخيرًا، بلغ معدل الثقة السائدة لدى الشباب اليمني 3.46 نقطة، على غرار السعودية، بينما بلغ معدل الثقة الخاصة بأداء المؤسسات 2.24 نقطة من أصل 4 نقاط.

Looking at the overall average of the two categories, we find that the average diffuse trust levels stood at 3.34 out of 4, which means it was between “trust to an extent” and “trust to a great extent”. On the other hand, the average performance-specific confidence levels stood at 2.20 out of 4, which was between “trust to an extent” and “do not trust to an extent”. While the average performance-specific confidence was somewhat higher than initially anticipated, it was still 1.14 below that of diffuse trust. Further, such high levels of national pride or diffuse trust should not stand in the way of demanding better and higher quality performance from public institutions.

Sub-regionally, North African youth’s average diffuse trust stood at 3.29, compared to an average of 1.83 performance-specific trust. West Asian youth’s average diffuse trust was also 3.29 while their average performance specific confidence stood at 2.02, slightly higher than that of North Africa. Youth of the Gulf averaged the highest diffuse trust level with 3.45 as well as the highest performance-specific confidence level with 2.75.

بالنظر إلى المتوسط العام للفئتين، وجدنا أن متوسط مستويات الثقة السائدة بلغ 3.34 نقطة من 4، مما يعني أنه وقع ما بين "أثق إلى حد ما" و"أثق إلى حد كبير". وعلى الجانب الآخر، بلغ متوسط مستويات الثقة الخاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة 2.20 نقطة من 4، أي كانت ما بين "أثق إلى حد ما" و "لا أثق إلى حد ما". وفي حين كان متوسط الثقة الخاصة بالأداء أعلى إلى حد ما مما كان متوقعًا في البداية، إلا أنه لا يزال أقل من مستوى الثقة السائدة بمقدار 1.14 نقطة. وعلاوة على ذلك، يجب ألا تقف هذه المستويات العالية من الثقة السائدة أو الانتماء الوطني في طريق المطالبة بأداء أفضل وأعلى جودة من المؤسسات العامة.

وعلى المستوى دون الإقليمي، بلغ متوسط الثقة السائدة لشباب شمال إفريقيا 3.29 نقطة، مقارنة بمعدل ثقة خاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة بلغ 1.83 نقطة. كما بلغ متوسط الثقة السائدة لشباب غرب آسيا 3.29 نقطة، بينما بلغ متوسط الثقة الخاصة بأداء مؤسساتهم الوطنية 2.02، وهو أعلى قليلاً من المعدل في شمال إفريقيا. وكان متوسط مستوى الثقة السائدة لشباب الخليج العربي أعلى مستوى للثقة السائدة في المنطقة بـ3.45 نقطة بالإضافة إلى أعلى مستوى ثقة خاصة بأداء المؤسسات العامة والذي بلغ 2.75 نقطة.

North Africa Sub-Region

Looking more specifically at the individual component scores for each country, we provide the highest and lowest trust/confidence levels for each country, divided by subregions. For North Africa, Egyptian youth noted the highest individual diffuse trust level, in the form of a 3.80 national affinity level, followed by Libya’s 3.72 national affinity level, and Tunisia’s national affinity with 3.61. Morocco and Algeria followed with 3.54 and 3.46, respectively, both for “national pride”. Mauritanian youth’s highest component was a 3.29 confidence level in the military. Finally, Sudanese youth’s highest component was a 3.17 national affinity level.

On the other hand, Algerian youth noted the lowest component, which was in the form of a 0.90 confidence level in elections. This was mirrored in low turnout and boycott calls. Egyptian and Mauritanian youth underscored the second lowest component, as Egyptian youth noted a 0.92 confidence level in labor unions and Mauritanian youth illustrated another 0.92 confidence level in healthcare services. Moroccan youth also had little confidence in elections with 1.19 confidence level, as Tunisian youth’s lowest trust component was a 1.20 confidence level in political parties, and Libyan and Sudanese youth illustrated similar disenchantment with elections with a 1.25 and 1.53 confidence levels.

National affinity and national pride were among the highest scoring indicators in this sub-region, yet the lowest scoring indicators were ultimately mostly institutions of democracy such as elections, labor unions, and political parties.

منطقة شمال إفريقيا

بالنظر بشكل أكثر تحديدًا إلى المؤشرات الفردية لكل بلد، خصصنا القسم التالي لأعلى وأدنى مستويات الثقة لكل بلد، مقسومة على المناطق الفرعية. وبالنسبة لشمال إفريقيا، كان الانتماء للوطن هو أعلى مؤشر لشباب المصري فيما يتعلق بفئة الثقة السائدة، حيث بلغ 3.80 نقط، يليه مستوى الانتماء الوطني لدى الشباب الليبي ب 3.72 نقطة، والانتماء الوطني لدى الشباب التونسي بـ 3.61 نقطة. يليها المغرب والجزائر بـ 3.54 و3.46 نقطة على التوالي، ل"الاعتزاز بالوطن". وكان أعلى مؤشر لدى الشباب الموريتاني هو 3.29 نقطة وكان لصالح مستوى الثقة في الجيش. وأخيرًا، كان أعلى مؤشر للشباب السوداني هو 3.17 نقطة وكان على شكل الانتماء للوطن.

وعلى الجانب الآخر، كان مستوى ثقة الشباب الجزائري بالانتخابات هو أقل مؤشر ب 0.90 نقطة، وقد انعكس ذلك فعلا في ضعف الإقبال على الانتخابات الأخيرة بالإضافة إلى دعوات لمقاطعة الانتخابات. وكان ثاني أقل مؤشر من نصيب كل من لشباب المصري والموريتاني، حيث بلغ مستوى ثقة الشباب المصري في النقابات العمالية 0.92، وهو نفس مستوى ثقة الشباب الموريتاني في خدمات الرعاية الصحية. كما لم يكن لدى الشباب المغربي ثقة كبيرة في الانتخابات والتي بلغ مستوى الثقة بها 1.19 نقطة، وكان أدنى مستوى ثقة للشباب التونسي هو 1.20 وكان من نصيب الثقة في الأحزاب السياسية، وأظهر الشباب الليبي والسوداني خيبة أمل في الانتخابات بمستويات ثقة بلغت 1.25 و1.53 نقطة على التوالي.

وعليه، فقد كان الانتماء للوطن والاعتزاز بها من بين أعلى المؤشرات في هذه المنطقة، بينما كانت المؤشرات المنخفضة بالغالب لمصلحة مؤسسات ديمقراطية مثل الانتخابات والنقابات العمالية والأحزاب السياسية.

West Asia Sub-Region

As for West Asia, Jordanian youth’s highest component came in the form of a 3.85 national affinity level, followed by a 3.69 and 3.6 for Lebanese and Iranian youth, in the same category. Palestinian youth’s highest individual indicator was a 3.58 national pride level, followed by a 3.56 national affinity level for Iraqi youth. Turkish youth’s highest individual component was a 3.36 national pride level, as Syria’s highest individual indicator came in the form of a 2.88 confidence level in the military, albeit data on Syria is slightly older than the other countries.

Syrian youth indicated the lowest confidence level in this sub-region, with a 0.93 confidence level in civil service, followed by 1.20 and 1.24 confidence level in political parties for each of Jordan and Iraq, respectively. Palestinian youth’s lowest individual indicator was a 1.31 confidence level in elections while Lebanese youth’s lowest indicator came in the form of a 1.35 confidence in healthcare services, also cited as the lowest by Iranian youth, with a 1.84 confidence level. Turkish youth’s lowest single indicator was a 2.27 confidence level in labor unions.

Similar to North Africa sub-region, the highest scoring indicators were mostly national affinity and national pride, whereas the lowest scoring indicators were split between institutions of democracy and those of public services.

منطقة غرب آسيا

أما بالنسبة لغرب آسيا، فقد كان أعلى مؤشر للشباب الأردني ب 3.85 للانتماء للوطن، يليه 3.69 و3.6 للشباب اللبنانيين والإيرانيين، في نفس المؤشر. وكان أعلى مؤشر فردي للشباب الفلسطيني هو الاعتزاز بالوطن ب3.58 نقطة، يليه معدل الانتماء للوطن لدى الشباب العراقي والذي بلغ 3.56 نقطة. وكان أعلى مؤشر فردي للشباب التركي هو 3.36 للاعتزاز بالوطن. وكان أعلى مؤشر فردي في سوريا على شكل مستوى ثقة في الجيش بلغ 2.88، وإن كانت البيانات المتعلقة بسوريا أقدم قليلاً من البلدان الأخر كما آنفنا سابقا.

وكان أدنى معدل ثقة لدى الشباب السوري، بمستوى ثقة بلف 0.93 في الخدمة المدنية، يليه مستوى ثقة 1.20 و1.24 نقطة في الأحزاب السياسية لكل من الأردن والعراق على التوالي. وكان أدنى مؤشر فردي للشباب الفلسطيني هو 1.31 نقطة كمستوى ثقة في الانتخابات، بينما بلغ أدنى مؤشر ثقة للشباب اللبناني 1.35 نقطة في خدمات الرعاية الصحية، والتي كانت أيضا أدنى مؤشر لدى الشباب الإيراني بمستوى ثقة بلغ 1.84 وكان أدنى مؤشر ثقة للشباب التركي هو 2.27 نقطة وكانت للنقابات العمالية.

على غرار لشمال إفريقيا، كانت أعلى مؤشرات الثقة في الغالب من نصيب الانتماء للوطن والاعتزاز به، في حين كانت المؤشرات الأدنى لمؤسسات ديمقراطية ومؤسسات الخدمات العامة.

The Gulf Sub-Region

Individual indicators for the Gulf sub-region were on average higher than those of the other two sub-regions. Qatari youth’s highest individual indicator was 3.97 national pride level, the highest single indicator across all countries. Yemeni youth also boasted a high level of national pride with 3.81, followed by 3.76 and 3.64 confidence level in the military for Saudi Arabian and Emirati youth. Kuwait youth’s highest indicator was a 3.59 national pride level, followed by 3.32 confidence level for the military for Omani youth, and finally a 3.24 national pride level for Bahraini youth.

On the other hand, Yemeni youth’s lowest single indicator was a 0.94 confidence level in labor unions, which was also the lowest single indicator for both of Kuwait and Bahrain with a 1 and 1.94 confidence levels, respectively. Omani youth’s lowest single indicator came in the form a 2.04 confidence level in the educational system. Saudi youth’s lowest indicator was a 2.40 confidence level in labor unions. As for Emirati youth, the lowest indicator was still a relatively high level of confidence (3.00) in the judicial system, as Qatari youth’s lowest indicator was also a high level of confidence (3.18) in the educational system.

منطقة الخليج العربي

كانت المؤشرات الفردية لمنطقة الخليج العربية أعلى في المتوسط في كل من المنطقتين الأخرى. حيث كان الاعتزاز بالوطن هو أعلى مؤشر فردي للشباب القطري ب3.97 نقطة، وهو أعلى مؤشر في جميع البلدان. وكان الاعزاز بالوطن أعلى مؤشر في اليمن أيضا وبلغ 3.81 نقطة، يليه مستوى الثقة بالجيش في كل من السعودية والإمارات ب 3.76 و 3.64 نقطة، على التوالي. وكان أعلى مؤشر لشباب الكويت هو الاعتزاز بالوطن والذي بلغ 3.59 نقطة يليه مستوى الثقة بالجيش لدى الشباب العماني ب 3.32 نقطة، وأخيراً مستوى الاعتزاز بالوطن لدى الشباب البحريني ب3.24 نقطة.

وعلى الجانب الآخر، كان أدنى مؤشر فردي للشباب اليمني هو مستوى الثقة في النقابات العمالية ب0.94 نقطة، والذي كان أيضًا أدنى مؤشر منفرد لكل من الكويت والبحرين بمستويات ثقة 1بلغت و 1.94 نقطة، على التوالي. وكان أدنى مؤشر فردي للشباب العماني من نصيب النظام التعليمي ب2.04 نقطة. وكان أدنى مؤشر ثقة للشباب السعودي هو مستوى الثقة في النقابات العمالية ب2.40 نقطة. أما بالنسبة للشباب الإماراتي، فقد كان أدنى مؤشر هو مستوى الثقة المرتفع نسبيًا (3.00) في النظام القضائي، وكان أدنى مؤشر للشباب القطري (3.18) للنظام التعليمي، وإن كان مرتفعًا مقارنة بالدول الأخرى.

باختصار، يمكن تقسيم أعلى المستويات في منطقة الخليج بين الاعتزاز بالوطن والثقة بالجيش، في حين كانت أدنى المؤشرات من نصيب النقابات العمالية، تليها الأنظمة التعليمية.

Most Pressing Challenges

The sub-regional brief analysis shows that national pride and national affinity were the highest scoring single indicators and notably higher than youth’s confidence in public institutions. In fact, the institutions which received the lowest performance evaluation were civil service, labor unions, elections, political parties, and healthcare services. Such poor evaluation is consistent to the major challenges facing people in the MENA region. With the COVID-19 global pandemic persisting, the three main and recurring challenges can be grouped under (1) economic challenges, including unemployment, price hikes, poverty, and deteriorating livelihoods; (2) government performance in terms of weak public services including health, education, and transportation, coupled with financial and administrative corruption; and (3) security related challenges including safety and political stability. The fact that these challenges continue to linger and remain under-addressed explains the low evaluation public institutions in meeting their objectives.

أبرز التحديات التي تواجه الشباب في المنطقة

وتبين أن الاعتزاز بالوطن والانتماء للوطن كانا أعلى مؤشرات فردية، وكانا أعلى بشكل ملحوظ من ثقة الشباب في المؤسسات العامة. في الواقع، كانت المؤسسات التي حصلت على أقل تقييم للأداء هي مؤسسات الخدمة المدنية والنقابات العمالية والانتخابات والأحزاب السياسية وخدمات الرعاية الصحية. ويتوافق هذا التقييم الضعيف مع التحديات الرئيسية التي تواجه الشباب في منطقة الشرق الأوسط وشمال إفريقيا. فمع استمرار انتشار جائحة فايروس كورونا، يمكن تصنيف التحديات الرئيسية الثلاثة على النحو التالي: (1) التحديات الاقتصادية، بما في ذلك البطالة وارتفاع الأسعار والفقر وتدهور سبل العيش؛ (2) أداء الحكومة من حيث ضعف الخدمات العامة بما في ذلك الصحة والتعليم والنقل، بالإضافة إلى الفساد المالي والإداري؛ و (3) التحديات المتعلقة بالأمن بما في ذلك السلامة والاستقرار السياسي. والحقيقة أن هذه التحديات لا تزال موجودة وغير معالجة وتفسر انخفاض تقييم المؤسسات العامة في تحقيق أهدافها.

Conclusion

The main take-aways of this brief report shows that young people in the MENA region boast high levels of pride in and belonging to their respective nations. But their confidence in public institutions in addressing their needs and meeting their objectives remains low, specifically, about 1.14 points out of 4, lower than their average diffuse trust levels. While the gap is clear, a tendency to overlook, downplay, deprioritize, or even ignore the challenges we face remains a trend in the region.

الخاتمة

الخلاصات الرئيسية لهذا التقرير الموجز تكمن في أن الشباب في منطقة الشرق الأوسط وشمال إفريقيا يتباهون بمستويات عالية من الاعتزاز والانتماء لدولهم. ولكن ثقتهم في المؤسسات العامة في تلبية احتياجاتهم وتحقيق أهدافها لا تزال منخفضة، وعلى وجه التحديد، حيث جاء معدل الثقة في المؤسسات العامة حوالي 1.14 نقطة أقل من متوسط مستويات الثقة السائدة. وفي حين أن الفجوة واضحة، إلا أن هناك بعض الميل إلى التغاضي عن التحديات التي نواجهها أو التقليل من شأنها أو تقليل أولوياتها أو حتى تجاهلها.

ولمحاولة تفسير هذا التناقض، هناك ثلاث نظريات رئيسية في الأدب السياسي السائد. تنص النظرية الأولى على أن القومية أو الاعتزاز بالوطن يتضاعف عندما تقارن الدول بين بعضها، مما يدفع مواطنيها للدفاع عن التقصير في بلدانهم. وتنص النظرية الثانية أن الهوية الوطنية للشعب - وبالاعتزاز بالوطن – تزداد عندما تواجه بلدانهم تحديات تتعلق بالأمن. وهذا يشبه النقاش حول "الأمن وحقوق الإنسان"، حيث يُعتقد أن حقوق الإنسان تتراجع إلى مكانة أقل أهمية عندما يكون الأمن هو الأولوية. وتشير النظرية الثالثة إلى أن الحكومات، بشكل ما أو آخر، قد غرست فينا فكرة أن انتقاد الأداء الحكومي يعني تلقائيًا انتقاد الدولة، وهذا بدوره ينعكس سلبًا على حب المواطن وانتمائه إلى بلده، وقد يصل حتى إلى حد "الانشقاق".