The Saudi Arabian-Iran Proxy War in Yemen

Introduction

Saudi Arabia and Iran’s interests are at two opposite sides in the region. Peter Salisbury concludes that the two states are in a scramble for regional influence, impacting many existing conflicts. Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain, and Yemen are examples of the two states attempting to advance their interests, with the last being the latest and most complex. When applying the Realist theory of International Relations, one can argue that Saudi Arabia and Iran are at a regional Cold War.

Rasmussen illustrates that a conflict is “an escalated competition at any system level between groups whose aim is to gain advantage in the area of power, resources, interests, and needs.” He adds that such groups have to perceive that the dimension of their relations is “mutually incompatible.” This discerption is agreed on by Holder and Henry, who added that two parties are at conflict when their actions in pursuit of their interests are to damage the other party. Katz and Lawyer assert, consequently, that the actions of one party have to impact their rival; otherwise, it is a difference, not a conflict. Saudi Arabia and Iran are at a competition to gain an advantage in the region, their interests are incompatible, and the actions of one directly affect the other. The question is what type of conflict?

Zbigniew Brzezinski defines cold war as “warfare by other (non-lethal) means.” Medhurst, Ivie, Wander, and Scott associate “rhetoric” with the idea of cold war, asserting that the means used are aimed at ensuring a full-scale war between the two competing, confronting, and rival parties does not erupt. Andrew Mumford adds that when two parties seek to advance their interests and strategic goals but avoiding a direct warfare, they engage in proxy wars, defined as “the product of a relationship between a benefactor, who is a state or non-state actor external to the dynamic of an existing conflict, and the chosen proxies who are the conduit for the benefactor's weapons, training and funding.” He illustrates that proxy wars are the “logical replacement for direct warfare.”

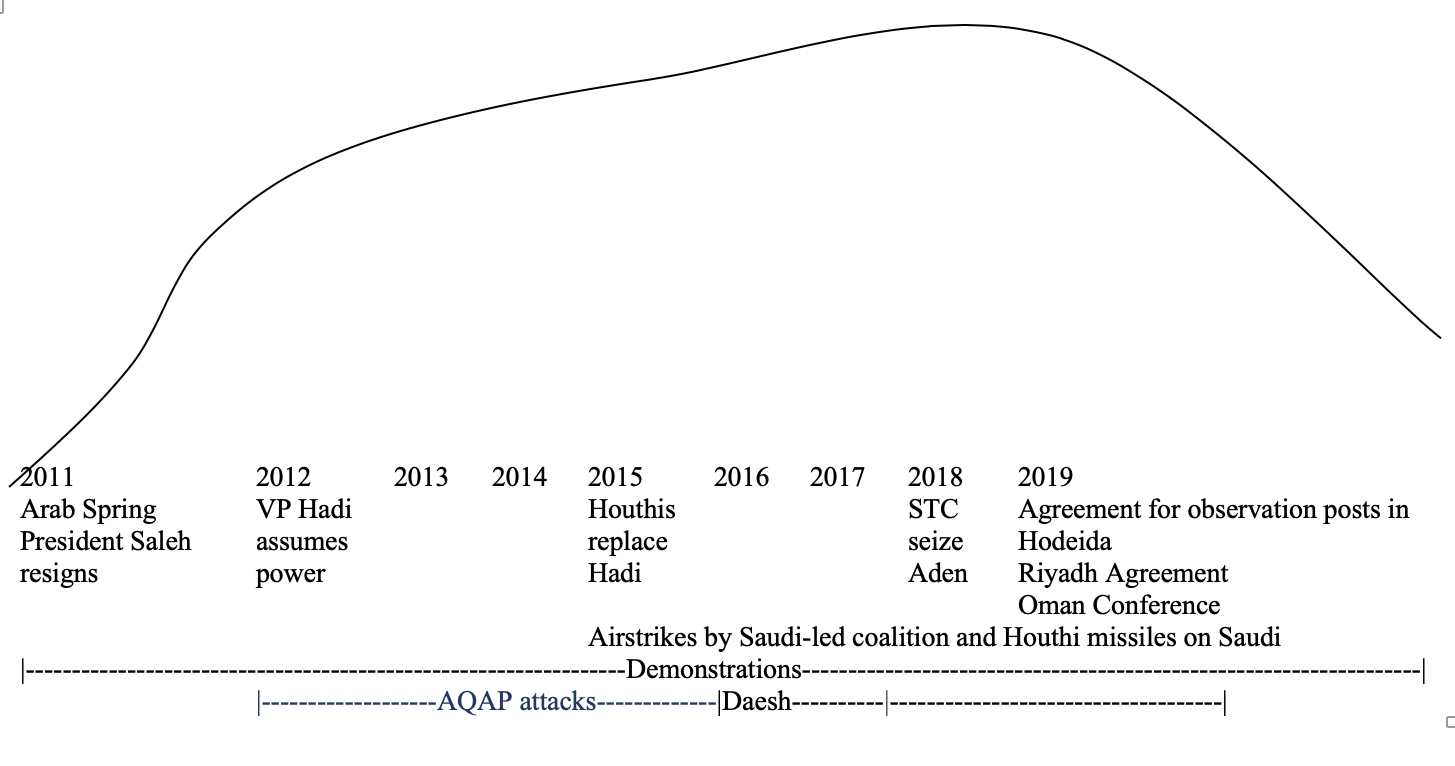

As such, Saudi Arabia and Iran are engaging in indirect war through proxies in Syria and Yemen, among others, in pursuit of advancing their own interests and strategic goals through a Middle Eastern Cold War. Of the many places where the two states engage in some level of rivalry, Yemen stands out as the most confrontational and brutal conflict, with Saudi Arabia deterring the Iran-backed faction: the Houthis. The conflict in Yemen is generally analyzed through one of three narratives: the Saudi-Iranian proxy war narrative, the sectarian narrative, and the AQAP/failed state narrative. This protracted conflict has seen numerous failed conflict management attempts, along with many intervening institutions. This paper analyzes the conflict, examines past and current conflict management strategies, assesses the various intervening institutions, and recommends the most relevant strategy that can best address the conflict.

Conflict Analysis

Cemile Aydin, Shahram Chubin and Charles Tripp, Gwenn Okruhlik, and Frederic Wehrey explored Saudi-Iranian relations with emphasis on rivalry and use of conflictual relations to gain internal support, especially amid the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, which many scholars define as the start of this rivalry towards religious legitimacy, regional security, and regional hegemony. Iran’s leaders in late 1970s and early 1980s declared its anti-West narrative, placing Saudi Arabia at the center of such rhetoric. Ayatollah Khomeini asserted that Saudi’s leadership failed to lead the Muslim World in the face of western control, and that, Iran had to exert its role as the rightful leader of the Ummah. Saudi, fearing the effects of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, decided to embrace Iran as an enemy to suppress internal issues and to create cohesion.

Following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, Iran began expanding its sphere of influence. This sphere of influence was manifested in Iran geographically surrounding Saudi, through alliances with Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Qatar, Bahrain, and Yemen. Simon Mabon writes in Saudi Arabia and Iran: Power and Rivalry in the Middle East that the US-led invasion of Iraq marked an integral era in the Saudi-Iran conflict, as they were allowed time and space to engage in proxy antagonism to advance their strategic goals. The Arab Spring provided an opportunity for the two states to extend their influence through a proxy war in Yemen. With Ali Abdallah Saleh’s regime collapsing, insurgency in Yemen expanded, with AQAP, Al Hirak Al Janoubi, Daesh, and the Houthis, among others found time and space for their movements. The involvement of Saudi Arabia and Iran through proxies further complicated the course of the conflict in Yemen.

Saleh’s deputy Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi was unable to deal with Jihadists’ movements, separatists’ activities, and the Houthis and security forces, who are loyal to former president Saleh, forced Hadi to flee Yemen and advanced from the south to the north, reaching Saudi’s southern border. Saudi Arabia led a coalition with 8 other mostly Sunni states, receiving logistical and intelligence support from the US, UK, and France, to restore Hadi’s government. They began launching air strikes against the Houthis, and supported the legitimate government’s forces. Meanwhile, Al Hirak Al Janoubi, a separatists’ movement are seeking independence for the south, to partition Yemen into its pre-unification days: East and West.

This multidimensional conflict also includes support from Iran to the Houthis, a revivalist movement representing Zaydi Shiites. Salibury’s research finds that the Houthis’ leadership are committed to the principles of Hussein Badr Al-Deen Al-Houthi, largely influenced by the Islamic Revolution of Iran. The group does in fact receive support from Iran, but the extent to which it takes orders is yet to be confirmed. Their prime objective is to deter any foreign intervention in Yemen, perceived to be Saudi’s “Yemeni government puppets.” In January 2015, they seized Hadi’s presidential palace, private residence, and the two headquarters of Yemen’s intelligence organization. They called for more political power, as the sanctions imposed by the international community remain ineffective in deterring them.

Figure 1: Source: Aljazeera, Reuters, World Energy Atlas, Critical Threats, March 2019

In recent months, the UAE, Saudi’s biggest ally in this conflict, left the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen due to financial constraints. Since Saudi cannot support any group besides the government of Hadi, its involvement remains mostly in the form of airstrikes and deterring attacks from the Houthis who continue to fire missiles from Saudi’s southern border. Saudi continues to do what is necessary to ensure the retention of Hadi’s government while defending attacks from the Houthis, backed by Iran.

Saudi Arabia wants to ensure the protection of its boarder by deterring Houthi attacks and ensuring the presence of an internationally recognized, legitimate government in Yemen under the leadership of president Hadi. The Houthis, who are supported by Iran, Hezbollah, and Al Quds Force, continue to target Saudi with drone and missiles strikes, the latest of which targeted ARAMCO, Saudi’s most important oil production site. Ultimately, the Yemen conflict’s complexity reached another level with the involvement of Saudi and Iran. Saudi Arabia’s proxy in Yemen is somewhat nonexistent after UAE’s retreat, diminishing the relevance of the coalition, and solidifying Saudi’s direct involvement under the umbrella of national security. On the other hand, Iran’s involvement is manifested in the Houthis as its proxy. The Houthis also seek to ensure that Yemen is alleviated from outside intervention by Hadi’s government allies; mainly Saudi. Riedel argues that the Houthis “embody what Iran seeks to achieve across the Arab world: the cultivation of an armed non-state, non-Sunni actor who can pressure Iran’s adversaries both politically and militarily.” The below table illustrates the main actors and their motivations:

Actor | Motivation | Alliances |

Saudi Arabia | Protection of its boarder and national security, and reinstate president Hadi | Yemeni president Hadi, Yemeni tribal leaders and religious leaders |

The Houthis | Deterrence of any outside intervention in Yemen, mainly from Saudi | Iran, Hezbollah, Al Quds Force, and security forces |

Iran | Advance its own geopolitical interests, enhance its sphere of influence, and weaken Saudi | The Houthis |

An Analysis of Previous Conflict Management Attempts

Previous conflict management efforts in Yemen have been centered around peace-talks, ceasefire, political transition/ power sharing, and mediation. The plethora of techniques utilized is not a surprise given the complexity and multidimensionality of the conflict, with the Saudi-led coalition and later Saudi alone engaging in direct cross-border armed conflict with the Houthis, sectarian separatist groups fighting, and an international effort against AQAP and other terrorist organizations.

First UN Special Envoy on Yemen

Similar to its efforts in Syria, the United Nations Security Council established the Office of the Special Envoy to the Secretary-General on Yemen in 2015. This office has aimed to provide necessary support to the Yemeni-led political transition through an inclusive engagement and participation of all demographic groups involved, including women, youth, the Houthis, and the Southern Hirak Movement. The UN also facilitated a National Dialogue Conference in January 2014, featuring delegates from all Yemeni regions and political affiliations. The delegates drafted the blueprints for a federal and democratic Yemen, based on the principles of good governance, rule of law, and human rights, which were to become the foundation for a new constitution to be drafted by a Constitutional Drafting Commission. While these efforts established an all-inclusive local vision for a better future for Yemen, it disregarded outside interventions and allegiances as well as their impact on intergroup dynamics. It also disregarded a far more important point, which was the ongoing armed conflict between various local groups and between the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis. All of which culminated in its failure to bring about proper transition in Yemen.

Former UN Special Envoy for Yemen Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed attempted repeatedly to establish a peace agreement amongst the disputing parties, but the Houthis and their allies the Saleh forces along with the Saudi-led coalition continued to disagree over the main points and objectives. In October 2016, Ould Cheikh Ahmed presented a peace plan which relied on a gradual transfer of presidential power to a new prime minister or a vice president, as the president position would become a limited, ceremonial position. The plan also featured a formation of a national unity government, a gradual removal of the Houthi-Saleh forces from the cities they had seized between 2014 and 2015, the formation of an international observation mission to verify this proposed withdrawal, and finally a gradual transition towards presidential and parliamentary elections.

The Second UN Special Envoy on Yemen

Following the 2018 coalition airstrikes on Hodeida, a coastal region, the United Nations represented by its newly appointed Special Envoy for Yemen, Martin Griffiths, attempted to negotiate a cease-fire. This cease-fire in Hodeida came after the Houthis seized the port that is essential for humanitarian aid along with Saudi carrying airstrikes on the port, albeit claiming them to be against the Houthis, according to Neil Patrick. Patrick adds that Saudi sought to halt the Houthi’s control over the port and their assaults on shipping in the Red Sea.

The cease-fire, also known as the Stockholm agreement, was limited to the Hodeida port on the Red Sea. The Stockholm agreement stipulated a cease-fire around Hodeida, a prisoner swap in Taiz, and a statement of understanding among all sides to form a committee to discuss the future of Taiz, which later came to be known as the Regional Deployment Committee (RDC). While direct fighting in the Hodeida port did stop, the confrontation increased in other areas.

Peter Salisbury, a renowned analyst on this particular conflict, characterizes the Stockholm Agreement as hard-won despite its shortcomings. He emphasized the importance of its success for future similar efforts. He argued that this agreement did not include any technical details on its scope, duration, or nature of the ceasefire to hostilities; specifications in relation to breaches; or any mechanisms for quick action points in the event any fighting restarts. Such points are integral in any ceasefire agreements, and their absence from the Stockholm Agreement left adequate space for the warring parties to reengage. In fact, the Houthis were not prevented from handing over the port to themselves, as they rendered Patrick Cammaert, the UN chair of the RDC, was overstepping his mandate, particularly that the meetings were held in areas controlled by the Yemeni government. Alistair Burt, the United Kingdom’s Middle East Minister, voiced his doubts over the resolution, arguing that it merely was enacted to build confidence between the disputing parties and to keep the RDC negotiations going. As such, one can argue that the UN Special Envoy, Griffiths, in this ceasefire agreement, had a long-term vision of the parties returning to the negotiation table that his plan was not solid to maintain and enforce the ceasefire that would enable such negotiations to happen. In fact, Griffiths himself spoke about his optimism and his confidence in his ability to bring the parties to the negotiation table. By that time, it had been almost two years following the failure of the last direct negotiation round. Griffiths’ plan had the support of the coalition partners.

It was rather clear that the international community, eager to resolve the conflict, was also thinking ahead with Griffiths beyond and disregarded whether the Stockholm Agreement stands still or fails. Foreign ministers of the United States, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates met to discuss the practical steps following the ceasefire in Hodeida. Gerald Feierstein analyzed that it was important to provide the necessary political and diplomatic support for Griffith to pursue his plan. But Feierstein’s analysis presumed, much like the international community, a larger level of political will among the major players in this conflict, namely Saudi, Iran, UAE, and the Houthis. Instead, he argued that the Yemeni population, feeling the effects of the conflict, would be very much be open to and support the plan. Though this assumption is valid, the general Yemeni population have lost their agency in this conflict shortly after the Arab Spring. Furthermore, the “quad meeting” and Feierstein’s article anticipated Saudi and UAE’s goodwill in both reconstruction and economic revival through a reintegration into the GCC, a proposal that appears unlikely, as the two states would be reluctant to re-engage Yemen into the GCC, particularly with Iran’s direct ties to the Houthis, who in Griffiths’ plan, would have a seat on the decision-making table, and with the poorly enforced ceasefire, would still have direct control over the Hodeida port, an important commercial port in Red Sea trading routes.

The United States' Role in Yemen

Looking at the role played by the United States in Yemen, a Congressional Research Service Report illustrates the US approached Yemen through the following action points:

1. Support for U.N. efforts to advance a political process;

2. Condemnation of Iran’s destabilizing role in Yemen;

3. Assistance for the coalition;

4. Sales of armaments and munitions to Gulf partners;

5. Counter-terrorism cooperation with the ROYG and Gulf partners;

6. Humanitarian Aid for Yemen

Former President Obama signed off on the “provision of logistical and intelligence support” to the Saudi-led coalition in their military operations in Yemen, and he announced the “Joint Planning Cell with Saudi Arabia to coordinate US military and intelligence support.” Perhaps the largest driver behind the US engagement was the operations against AQAP and Daesh in Yemen, as they worked closely with the Republic of Yemen Government and allies in the region in conducting airstrikes on AQAP and Daesh. As such, the United States’ management of the Yemeni conflict prioritized the fight against terrorist organizations, and one can argue that in this regard, they have been relatively effective.

The European Union's Role - Mediation

The role played by the European Union in Yemen has been through the realms of mediation. Mediation is defined as a “form of negotiation in which a third party helps the disputants to find a solution that cannot otherwise find by themselves. It is a three-sided (or more) political process in which the mediator builds and then uses relations with the other parties to help them reach a settlement” Mediation seeks to highlight a set of mutually beneficial settlements, but a major prerequisite is forming formidable diplomatic relations prior to initiating these efforts, something that arguably Ould Cheikh Ahmed and Griffiths failed to do. In fact, Griffiths has accused the Saudis and the Houthis of war crimes in Yemen. Though the accusations are valid, they hinder his efforts to broker a peace agreement through direct face-to-face negotiations.

Natalie Girke writes that the European Union started its mediation efforts through its Delegated Mediation Support Team (MST) following the 2011 uprising and concluded with the failure of the 2014 National Dialogue Conference. Girke outlines that the MST managed to establish mediation awareness in Yemen, but it was short-lived and did not manage to realize its full potential. She reasons that the UN Special Envoy sidelined the EU out of the process.

An Analysis of Current Conflict Management Efforts in Yemen

Though Saudi was seemingly left alone when the UAE left the coalition for financial concerns, recent developments show a different reality. Current conflict management efforts taken in Yemen are now leaning more towards power sharing and political restructuring. The past few months have seen some positive efforts to bring a settlement to the conflict. The Yemen’s internationally recognized government agreed with the Houthi rebels to set up observations posts to observe the ceasefire in Hodeida and de-escalate the areas prone to conflict, an effort that was supported by the UN Hodeida mission.

Two weeks following this agreement, the Yemeni government with its President Hadi who supported by the broader international community and Saudi signed a power-sharing agreement with the southern separatists the Southern Transitional Council (STC) headed by Al Zubaidi, who is backed by the UAE. The agreement, known as the Riyadh Agreement, seeks to stop the fighting and to bring stability to Yemen. In this agreement, the Yemeni government will enable the separatists to assume equal representation while their security forces will join in with the government forces under the defense and the interior ministries.

The third major development in recent months came in one week following the power-sharing agreement when the Saudis and the Houthis are believed to have held an indirect, secret peace talks on November 13th, 2019 to end the war in Yemen. These negotiations have taken place in Oman who served as the mediator. Reports indicate that the talks followed on to a video conference two months ago.

When we cross-examine UAE’s withdrawal from the Saudi-led coalition and their reentry into the scene through backing the southern separatists and co-brokering the Riyadh Agreement with Saudi, we find a positive and a negative side to this turn of events. Salisbury asserted that if the Riyadh Agreement is adopted well, it would prevent a “war-within-a-war” between Hadi’s government and the STC, and it would also provide credibility to future government negotiations with the Houthi rebels, which followed a week later. On the other hand, Salisbury highlighted that the deal is much open to interpretation, loosely worded, and has an ambitious timeline.

On the other hand, Gamal Gasim, a Yemeni-American political science professor, downplayed the agreement, reiterating the fact that the disputants are merely extensions of one or other countries in the region. He added that the Southern Separatists, though backed by the UAE, are still likely to pursue their long-term goal of succeeding and establishing their own state. Gasim sees the strategic objectives of the Riyadh Agreement through two scenarios: first, it may strengthen the coalition in facing the Houthis who are backed by Iran, particularly that they have achieved some gains against Saudi recently. Alternatively, it may help maintain the alliance and utilize it to enhance the Saudi-UAE geopolitical positions in plausible negotiations with Iran and the Houthis. Said Thabet sees another scenario in which Yemen is partitioned into a northern state under Saudi influence and a southern state for the STC to be directly overseen by the UAE. Thabet does not anticipate any STC rejection to this proposal since they long sought to achieve this. This proposal, however, presents complications for the situation involving the Saudi-Houthis stalemate.

Assessing the Intervening Institutions

There have been a number of intervening institutions in the Yemeni conflict since its inception. The list of intervening institutions or actors include Saudi Arabia, Iran, the UAE, the United States, the United Nation through Office of the Special Envoy to the Secretary-General on Yemen, the European Union, and the GCC and coalition member including Oman, excluding local actors such as the Houthis, Hadi’s government, security forces, and the STC. A Human Rights Watch report indicates that the coalition members, involved in unlawful attacks, have avoided international legal liability by refusing to provide any information related to the role played by their forces in these attacks.

The previous sections illustrated the roles played by these intervening actors. This section assesses their strengths and weaknesses according to what literature outlines as effective conflict management actor. Robert Zikmann indicates that an effective institution in conflict management understands the conflict and adopts an active response such as domination, distributive bargaining, compromise, and integrative bargaining, as opposed to a passive response such as denial, avoidance, or capitulation.

Klein, Reiners, Zhimin, Junbo, and Šlosarčík illustrate that major powers adopt one of three diplomatic strategies: unilateralist, bilateral, and multilateral. Applying that onto conflict management, we can argue that an effective intervening actor has the ability to leverage relations, whether bilateral relations or more effectively, multilateral relations. Hampson and Zartman focus on the actors’ ability to adopt the appropriate narrative and shift between them when needed. One of these narratives, straight talk, is helpful in producing alternatives to a negotiated settlement. BATNA or Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement are security points[5], which aims at illustrating the, usually undesired, alternative.

Olson and Pearson argue that a successful intervening actor are separate, neutral, an outsider-impartial, and sovereign/independent. They have the ability to bring parties to an agreement through repeated attempts and in the presence of an external military intervention[6]. This last point can be extended to encompass the actors’ ability to maintain the agreement and peace. Other aspects for the strength of an intervening actor include political will and playing a stabilizing role. The following table illustrates the extent to which the intervening actors have fulfilled effective roles in each of these factors. They are assessed on a scale of 1 to 5, whereby 1 means lowest performance/ ability and 5 means highest performance/ ability, for each category to calculate a score out of a total of 65.

Category and commentary | Saudi Arabia | Iran | UAE | US | Special Envoy Ahmed | Special Envoy Griffiths | EU | GCC and coalition |

Understands the Conflict: Complete understanding of the conflict and its consequences | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

Adopts an active response: Proactively seeking to manage the conflict | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

Build relations with stakeholders: Meaningful bilateral and multilateral relations with all parties involved | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

Has the ability to leverage relations: Using them to broker a settlement | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

Adopted an appropriate narrative: Approaching the conflict through relevant narratives to its nature and the parties involved | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

Has the ability to shift between narratives: Can switch the tone when needed to arrive at the best outcome | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

Separate, neutral, and impartial: Not a perpetrator in the conflict; can sideline their gains for a productive management | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 |

Sovereign/independent: The actor is the sole decision-maker of their own actions | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 |

Persistence: Attempting repeatedly until the sought objective is met | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

Ability to maintain the agreement and use military intervention if needed: Can ensure the sustainability of the agreement and use force when needed | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

Ability to maintain peace: Can uphold ceasefire and ensure infighting does not rebreak | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

Political will: Fully determined to bring a settlement | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

Plays a stabilizing role: The actor is stabilizing the conflict and is not inflecting any counterproductive or destabilizing actions | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

Total/65 | 38 | 29 | 35 | 45 | 59 | 63 | 41 | 39 |

Looking at the table above, we find that there are areas of strength and areas of weaknesses, individually and collectively. Overall, Special Envoy Griffiths with his office top the list as the most effective intervening actor, with Ould Cheikh Ahmed slight behind. This is because the former envoy did not manage to uphold his relations with all parties involved, and he was not as persistent as Griffiths. In fact, the Houthis demanded his replacement, as he failed to deal with them properly and failed to keep Saudi, Iran, and others accountable, unlike Griffiths who was vocal in his condemnation.

Other major actors, namely the US and the EU have limited their involvement to rather underwhelming roles. The United States focused on the fight against terrorism, which is the basis for their relatively high score. On the other hand, they contributed largely to the coalition, which played a counterproductive and destabilizing role. The EU were fulfilled after their incomplete mediation efforts. Both actors have not adopted an active response, did not invest much time or effort in building relations, were not persistent, did not invest in maintaining any agreements or maintaining peace, and they lacked the political will.

Saudi, Iran, the UAE, and the coalition countries have shown a number of weaknesses in their interventions. They did not separate their interests from the conflict; they were sporadically inactive, but when they were active, they played a rather destabilizing role. They also did not build meaningful and useful relations, they were inflexible, they were not persistent in the positive sense, and they were not able to uphold any agreement or ceasefire, let alone, peace. The only exception is recent efforts that brought Hadi’s government with the STC and then the Saudis with the Houthis, but even that can inflect further instability to the conflict going forward.

Is Stabalization the Answer

In the midst of geopolitical talk and conflict management efforts, the magnitude of the humanitarian crisis in Yemen often gets sidelined. HRW estimates 7,000 civilian deaths, 11,000 in casualties, and 3 million women and girls at the risk of violence, and 14 million face the risk of starvation and death. These numbers are for 2018 alone, as the actual total numbers are much higher in terms of deaths and casualties. These numbers, coupled with the ongoing insurgency, intergroup fighting, and cross-border war, necessitate efforts to stabilization as a step for further conflict management efforts. The US government, through the Stabilization Assistance Framework, defines stabilization as a “political endeavor involving an integrated civilian-military process to create conditions where locally legitimate authorities and systems and peaceably manage conflict.

Stabilization is a prerequisite to restructuring/ rebuilding and state building efforts. It can be effective in stopping the infighting, and it can maintain peace. It celebrates inclusion for all stakeholders, and it is less financially consuming and far better viewed internationally, unlike its counterpart, full military intervention. Stabilization also serves as a bridge for a longer-term reconstruction and reconciliation. The success for stabilization is contingent on local and international partnerships, to essentially approach the conflict and its burden on the local people cooperatively[4]. It would not be fully successful without some military presence on the grounds, which would seek to ensure fighting does not break again.

Stabilization would be effective in Yemen for a number of reasons. First, stabilization has seen relative success in Iraq and in Syria, two nearby states going through similar issues. In both states, the United States spearheaded stabilization efforts and forged effective, and necessary, partnerships with local actors, mainly to deter terrorist organizations, such as in Syria and in Iraq, two of the most recent US engagements in the Middle East region. In Syria particularly the US’ alliance with the Syrian Kurds proved effective in territorially defeating Daesh, albeit served as a building block for a Turkish offensive on the-now-enhanced Syrian Kurds. In Iraq, the anti-ISIS coalition was supported directly by the UN Assistance Mission to Iraq (UNAMI), proving for relative success too. As such, the US appears more in favor for such an engagement as opposed to its alternative, military intervention, which not only has been too costly on the US budget, but it has also harmed the US’ image in the region.

Another reason why stabilization would be effective in Yemen is that stabilization tends to be inclusive in nature. In this context, recent talks between the Hadi Government and the STC, between the government and the Houthis, and between the Saudis and the Houthis pave the way for further collaborative effort for stabilization, especially following the agreement between the first two groups to joining their arms together under the Ministries of Defense and the Interior. With that, the political will, internally, is welcoming for such a plan.

For this plan, the United Nations may also see necessary that it deploys a peacekeeping mission. Its special envoy on Yemen also has to maintain its role as the integrated and impartial broker. Griffiths ought to keep the parties talking, periodically, to facilitate the next steps for Yemen. These two subfactors are necessary to counter the possibility of spoilers. Spoilers are defined as “groups and tactics that actively seek to obstruct or undermine conflict settlement through a variety of means, including terrorism and violence.”

Possible spoilers for stabilization in Yemen are Saudi, UAE, Iran, the Houthis and resurgent terrorist organizations such as the AQAP and Daesh. The Hadi government and the STC are not included in this list due to their allegiances to bigger actors in the region, namely Saudi and UAE. The Houthis are included, however, as they may still act independently of Iran. The complexity and multidimensionality of the Yemeni conflict makes predictive analysis difficult. Nonetheless, peacekeeping missions along with the joint forces of STC and Yemeni government, and perhaps with US support, can act swiftly to any terrorist spoilers.

Griffiths, on the other hand, has a large role to play, to keep Saudi, Iran, and the UAE accountable and monitor their actions. For that, he would require the support of the international community to back his vocal statements against any potential spoilers on their part. Saudi and UAE established quasi-mandates over the north and south parts of Yemen, respectively, and if they anticipate that this proposal may hinder their geopolitical stance, they may inflect destabilizing actions. Griffiths would have to mediate between the Houthis and the Saudis to establish important guarantees. If Saudi had claimed its motivation in engaging in Yemen was driven by national security and if the Houthis claimed their motivation was the rejection of any Saudi involvement, then a prolonged ceasefire and an agreement to guarantee neither of that happens would propel the two parties to disengage.

Ultimately, it is important to note that Saudi Arabia and its coalition have been losing much support inside of Yemen as well as internationally, following the murder case of journalist Jamal Khashogji and careless airstrikes on civilian targets. On the other hand, Iran as destabilizing as it is, has utilized the media better. The more civilian casualties, the more Yemeni people seem to stand behind the Houthis. Saudi Arabia, by contrast, are appearing in the media somewhat arrogantly and their killing of children, women, civilians, and the destruction of many schools and hospitals have been a card used effectively by the Iranian-backed propaganda.

Bibliography

Aydin, Cemil. The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History. Harvard University Press, 2017.

Brown, Frances Z. “Dilemmas of Stabilization Assistance: The Case of Syria.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. October 26, 2018.

Brzezinski, Zbigniew. “The Cold War and Its Aftermath.” Foreign Affairs 71, no. 31 (1991-1993).

Clausen, Maria-Louise. “Understanding the Crisis in Yemen: Evaluating Competing Narratives,” Italian Journal for International Affairs 50, no. 3 (2015).

“Conflict Analysis Framework: Field Guidelines and Procedures.” GPPAC. November 2017.

Croker, Chester, Hampson, Fen Osler, and Pamela Aall, Taming Intractable Conflicts. US Institute of Peace Press, 2004.

Dorsey, James M. “The UAE Withdraws from Yemen.” BESA, August 4, 2019. https://besacenter.org/perspectives-papers/uae-yemen-withdrawal/.

Feierstein, Gerald M. “New Hope for Resolution of Yemen Crisis.” Middle East Institute. June 26, 2018. https://www.mei.edu/publications/new-hope-resolution-yemen-crisis.

Gause, F. Gregory. “Ideologies, Alignments, and Underbalancing in the New Middle East Cold War.” Cambridge University Press 50, no. 3, (2017): 672-675.

Gavlak, Dale. “Efforts Ramping Up to Resolve Yemen Conflict Following Saudi Attacks.” VOA, October 3, 2019. https://www.voanews.com/middle-east/efforts-ramping-resolve-yemen-conflict-following-saudi-attacks.

Hampson, Fen Osler and I. William Zartman. “The Tools of Mediation and Negotiation.” In Crocker et al., Managing Conflict in a World Adrift, 381. USIP Press and CIGI Press, 2015.

Klein et al. “Diplomatic Strategies of Major Powers: Competing Patters of International Relations? The Cases of the United States of America, China, and The European Union.” Mercury, no. 2, (2010): 8-9.

Mabon, Simon. Saudi Arabia and Iran: Power and Rivalry in the Middle East. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Medhurst, Martin J., Ivie, Robert L., Wander, Philip., and Rober L. Scott. Cold War Rhetoric: Strategy, Metaphor, and Ideology. Michigan: Michigan State University Press, 1997.

Mumford, Andrew. “Proxy Warfare and the Future of Conflict.” The Rusi Journal 158, no. 2 (2013): 40-46.

Newman, Edward and Oliver Richmond. Challenges to Peacebuilding. Tokyo, United Nations University Press, 2016.

Olson, Marie and Frederic S. Pearson. “Civil War Characteristics, Mediators, and Resolution.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 19, no. 4 (2002).

Parello-Plesner, Jonas. “Post-ISIS Challenges for Stabilization: Iraq, Syria, and the U.S. Approach.” Hudson Institute. August 2018.

“Peace Deal Announced Between Yemeni Government, Separatists.” AlJazeera. November 5, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/peace-deal-announced-yemeni-government-separatists-191105145143441.html

Riedel, Bruce. “Who are the Houthis, and Why are we at War with them?.” Brookings, MARKAZ, December 18, 2017.

Salisbury, Peter. “Yemen and the Saudi–Iranian ‘Cold War’.” Catham House the Royal House for International Affairs, (2015).

“Saudi, Yemeni Houthis Hold ‘Indirect Talks’ in Oman to End War.” AlJazeera. November 13, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/saudi-yemen-houthis-hold-indirect-talks-oman-war-191113160747944.html

Sharpe, Jeremy M. “Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention.” Congressional Research Service, March 21, 2017.

Sharpe, Jeremy M. “Yemen: Civil War and Regional Intervention.” Congressional Research Service. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/mideast/R43960.pdf.

Shyoukhi, Nael. “Saudi Project Resolve, Flash Military Might After ARAMCO Attack.” Reuters, September 23, 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-saudi-nationalday/saudis-project-resolve-flash-military-might-after-aramco-attack-idUSKBN1W824G

“Special Envoy Yemen.” UN Political and Peace Building Affairs. Accessed December 7, 2019. https://dppa.un.org/en/mission/special-envoy-yemen.

“UN Envoy for Yemen Holds Briefings.” AlJazeera. September 16, 2019.https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/envoy-yemen-holds-briefing-190916153119992.html.

Ward, Alex. “The Week in US-Saudi Arabia-Iran Tensions, Explained.” Vox, September 20, 2019. https://www.vox.com/world/2019/9/20/20873672/trump-saudi-arabia-iran-oil-missile-drone.

“War in Yemen – Global Conflict Tracker.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed December 8, 2019. https://www.cfr.org/interactive/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/war-yemen.

Wintour, Patrick. “Yemen Ceasefire: New UN Resolution Seeks to Save Agreement.” The Guardian. January 16, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jan/16/yemen-ceasefire-un-urgently-tries-to-prevent-collapse-of-agreement

Yayboke, Erol, Melissa Dalton, and Hijab Shah. “Pursuing Effective and Conflict-Aware Stabilization: Partnering for Success.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. April 30, 2019.

“Yemen Crisis: Why is there a War?.” BBC News, March 21, 2019.

“Yemen Warring Parties Set Observation Posts in Hodeibah: UN.” AlJazeera. October 23, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/yemen-warring-parties-set-observation-posts-hodeidah-191023144504481.html

Younes, Ali. “Will Yemen’s Southern Peace Deal Really Help End The War?.” AlJazeera. November 5, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/yemen-southern-peace-deal-war-191105131251313.html.

Zartman, I. William and Saadia Touval. “International Mediation.” in Leashing the Dogs of War. US Institute of Peace Press, 2007.

Zikmann, Robert V. “Successful Conflict Management.” In Construction Conflict Management and Resolution, edited by Peter Fann and Rod Gameson, 54. London: Chapman & Hall, 1992.