What IF Youth Led the MENA Region – Wave II

Survey of Youth Perceptions

In the Spring of 2022, MENAACTION launched a periodic survey to gauge respondents’ perceptions on political, socioeconomic, and environment related factors. This survey explores how the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region would look like, politically, economically, and environmentally if youth were its leaders. In June 2023, MENAACTION conducted the second wave of the survey to extrapolate changes between the two years.

The second wave was implemented in partnership with NAMA Strategic Intelligence Solutions, and it looked to achieve the following objectives:

Track youth’s perceptions in terms of a series of political, economic, and environmental governance matters;

Provide a picture of how the region would look like if youth were to have a wider space to assume their roles as political, economic, and environmental decision- makers; and

Understanding the major issues facing youth in the MENA region and their root causes to essentially provide policy recommendations that can effectively address these challenges.

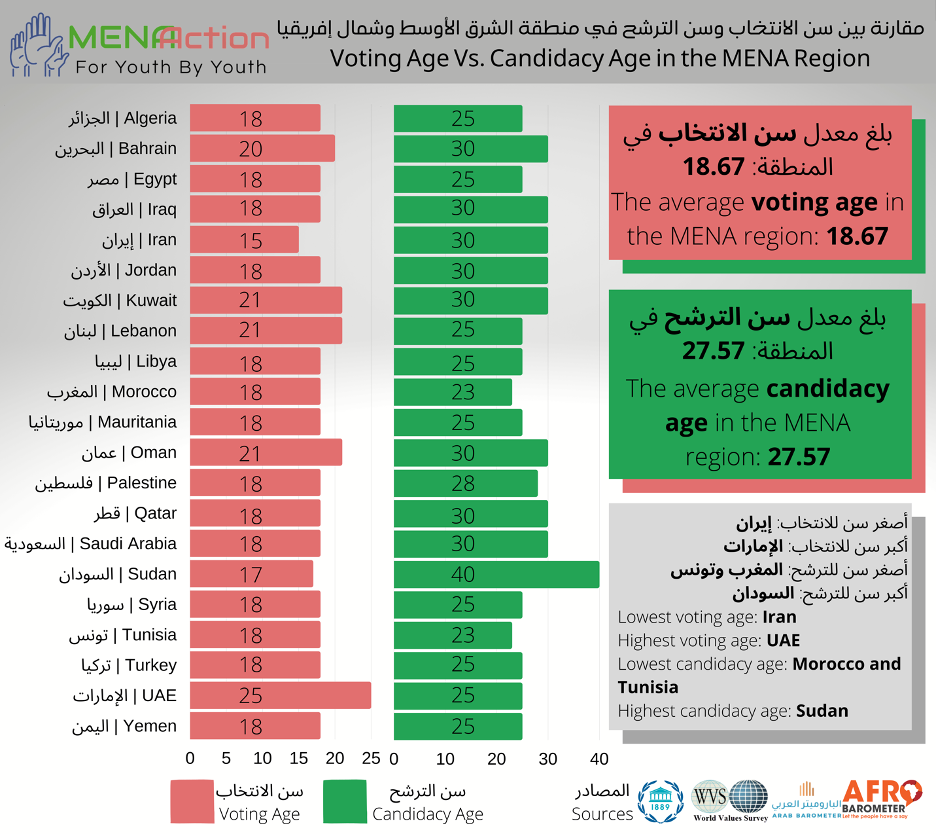

The total achieved sample is 2,237 respondents from 19 countries, namely Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Sudan, and Tunisia from North Africa; Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria from the Mashreq; and Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Yemen from the Arab Gulf.

Looking at demographic breakdown, the sample featured a 50-50 male to female ratio. The sample also comprised of 65.3% of respondents aged 18-34 and 34.7% of individuals aged 35 and older. Additionally, 52.5% of the respondents hold a bachelor’s degree, 13.2% hold a master’s degree or higher, 12.7% hold a diploma or completed 2 years of college, 15.1% completed secondary education, 4.8% underwent vocational or technical training, and 1.7% completed basic or elementary education.

Moreover, 50.7% of the respondents were employed, either full time or part time, along with 11.6% who were self-employed; 19.4% were unemployed; 9.9% were current students; 7.6% housewives; 0.4% were unable to work due to a disability; and 0.3% retired.

The survey was conducted online, using KoBotoolbox. MENAACTION ran paid promotions on its Facebook page to acquire respondents. MENAACTION faced a number of challenges during the data collection phase. Initially, the survey was advertised in all countries across the MENA region; however, a number of countries did not record any responses, propelling MENAACTION to approach CSOs in these countries to help with outreach. Secondly, certain countries were recording low participation rates. As such, MENAACTION focused more promotions in these countries along, which resulted positively. Finally, the male to female ratio was lower than the regional average; therefore, MENAACTION weighted the responses to ensure equal representation.